California Police Shift Policies on Responding to Mental Health Crises

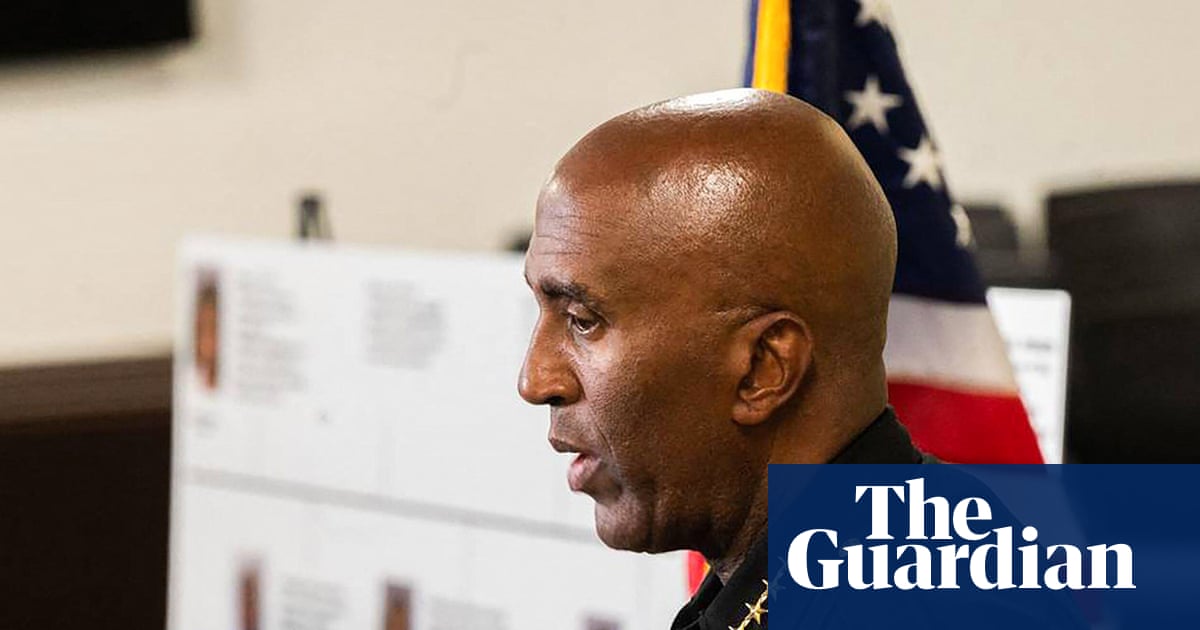

In recent policy shifts, several California law enforcement agencies have changed how they respond to mental health crises. Sacramento County Sheriff Jim Cooper announced in February 2026 that deputies will only intervene in mental health calls if a crime has been committed or is in progress, or if someone other than the person experiencing the crisis is in imminent danger. In May, El Cajon Police Chief Jeremiah Larson implemented a similar approach for San Diego County.

Other departments like Ventura County Sheriff's Office and Long Beach Police Department have stated officers will respond to every call but may leave if no crime or imminent threat is present. These changes come after a 2024 federal court ruling held Nevada officers liable for the killing of Ray Anthony Scott, a man with schizophrenia, highlighting the risks of police involvement in mental health incidents.

Between 2015 and 2024, US police killed 2,057 people experiencing mental health crises, accounting for about 20% of all police killings; California had at least 274 such deaths during that time. To provide alternatives, San Diego County's Psychiatric Emergency Response Team (PERT) expanded from 23 to about 70 clinicians. PERT co-responds with police, employing heat map deployment strategies and reports over 90% success in de-escalation and connecting people to resources, though it is not always available.

When police decline to intervene, dispatchers can direct callers to 988 or the San Diego Access and Crisis Line. The 988 service is able to diffuse crises without police involvement in more than 90% of cases, offering a critical resource for managing mental health emergencies safely.